A bill in Congress paved the way for my citizenship (Part 2)

By Metty Vargas PellicerWhen America got involved in the Cuban Revolution against Spain, it got involved in the Philippines who was also waging a similar war of independence. Fighting a common enemy, the Philippine Revolution joined forces with America. It facilitated the surrender of Manila and the rest of the Philippines to end the Spanish-American War. Aguinaldo then proclaimed Philippine Independence from Spain on June 12, 1898.

But as we all know, the Philippine Revolution was betrayed. Our representative was shut out from the negotiations at the Treaty of Paris. For $20 million, America’s spoils from the war were the Philippines, together with Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, Islands in the Caribbean-St. Thomas, St. John and in Oceania-the Marianas, Samoa, etc. The U.S. granted Cuba its independence after a brief military occupation, but decided to retain the Philippines. Essentially one colonizer took over for another. Aguinaldo refused to recognize it, and the Philippines continued a guerrilla war with a new enemy. We were of course woefully overpowered and the Philippine-American War was concluded with Aguinaldo’s capture on March 23, 1901. President McKinley justified annexation as a fulfillment of America’s Manifest Destiny, “to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them, and by God’s grace do the very best we could by them, as our fellow-men for whom Christ also died,” never mind that we were already Catholics for 300 years!

American colonization and shifting U.S. immigration policies created havoc in our Nationality classification.

We had been on this continent since the days of the Galleon trade between Acapulco and Manila from 1572-1815. Sailors on the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Nuestra Senora de Esperanza had jumped ship on the California coast at Morro Bay and had been known to settle there since 1587. A continuous settlement had been in existence in Louisiana since 1764, the Manila men at Saint Malo. Filipinos were nationals of Spain and governed through Mexico, New Spain, and in Louisiana we were under French governance.

After 1898, under U.S. occupation, we were U.S. nationals with unrestricted immigration. This first wave of immigration brought the members of the Philippine elites as scholars of the government, the Pensionados, and the disadvantaged members of the class spectrum, as agricultural workers in Hawaii and California, and laborers in the salmon canneries of Alaska, the Manong generation.

During the Commonwealth, from 1935-1945, we were aliens, and restricted from immigration. However, at the outbreak of WWII, citizenship was granted to enlisted men in the Navy but their role was limited to stewards and service workers. Because of the base agreement, recruitment continued in the U.S. Navy after Philippine Independence from the U.S. was granted on July 4, 1945, until 1992.

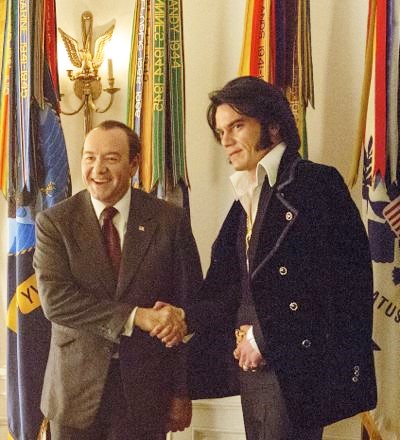

The Vargas clan and their families in Paris. Metty’s three brothers and four sisters are all living the American Dream due to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

Post-World War II, the War Brides Act brought the spouses of U.S. servicemen.

The Immigration Act of 1952 provided for family reunification, and an exchange visitor program for nurses. Mommy Pellicer participated in this program and trained in the U.S. for two years.

And this brings us to the Immigration Act of 1965.

The Reagan era saw the passage of Immigration and Reform Act of 1986, which granted amnesty to undocumented aliens.

American colonization and education did not make us Americans, even as we have wholeheartedly embraced American popular culture, in music, TV, the movies, fast food, and fashion

As immigrants, adjusting to this country involved a rude awakening to racial prejudice. In the ‘60s, a friend driving through North Carolina was denied purchase of milk at a convenience store. Mixed marriage was not legal in Georgia. A friend who bought a house in a white suburb of Clayton County, had eggs thrown at his front door and a cross burnt at his front yard. I had patients who asked to switch to a white male doctor directly. I had experienced discrimination on two fronts, as a woman and as a colored individual.

Filipinos of my generation are still influenced powerfully by colonial mentality. This is reflected in measuring our self-worth and what is desirable in the paradigm of our powerful colonizers. In physical appearance we value European/ American features. Don’t we all check a newborn, and beam with bigger pride when its nose is high or its skin, fair? We like to show off our westernized lifestyle in our choice of entertainment, sports, in our homes, our clothes, in the kitchen, in the vacation holidays we took.

In pursuit of the American Dream, we quickly assimilated the doctrine of consumerism, and credit. It was incredible and truly a culture shock, to realize that it was advantageous to have debt, in order to establish our financial stability and worth. In the Philippines, it was shameful to have debts, and only the very rich could afford to pay cash on a car. But, suffused with more cash than we ever had and with new found value in credit, we went on a buying spree. We strutted in our new Mustangs or GTOs. I couldn’t drive yet, but I bought a silver Camaro, for $50 down payment, and the rest of $2000 cost on credit. The women stocked up on Louis Vuittons, and Chanels, and perfumes, Jean Patou’s Joy and 1000. It was heady and exhilarating. We got married and had children. We felt the enormous responsibility to provide security and the best opportunity for them. By this time we had acquired a mortgage, credit cards, and debt. Our resolve to go back to save the health of the Philippines wavered. The news from home under martial law, and the repression of the Marcos regime made a decision to return foolhardy.

I completed my residency, I had a mortgage, a husband and a daughter and life was good. Then one day, my world ended. I got a deportation order! My J-1 visa had expired after completion of my residency training. Panic! Fortunately, Johnny knew the ways and means. He had a friend who worked in the office of Clarence Long, the congressman of our district in Baltimore. He sponsored a bill in Congress petitioning a permanent resident visa for me, the precious green card. That provided a pathway to citizenship, and in 1980, I was sworn in as a naturalized citizen of the USA.

In 2006, I co-chaired Georgia’s celebration of the Centennial of Filipino American Immigration. The celebration brought together for the first time, 15 Filipino organizations from the entire state. It was a very proud moment for Filipinos in Georgia. Everyone set aside regional consciousness and rivalry. On that occasion, we did not see ourselves as Tagalog, Bisaya, Bicolano, or Ilocano. We came out as a Filipino to celebrate our culture. We hosted a public festival of food, dance, song, martial arts, and handicrafts at the recently opened Atlantic Station. We needed to introduce ourselves to our community.

The author delivered this speech in Atlanta on the occasion of the 119th Celebration of Philippine Independence on June 12, 2017.

Part 1: Filipina doctor Metty Pellicer fearlessly finds herself in America

© 2017 The FilAm