My sister Myrna

In my mind’s eye, I can see my ‘ate,’ or older sister Myrna here, possibly as a ‘babaylan,’ part of a religious community more solidly rooted in folk beliefs than the Catholic Church and more empowering of her as a woman. I remember attending her 25th anniversary celebration as a nun with the congregation of the Immaculate Cordis Mariae. The occasion was marked by a renewal of her vow, along with those of six other nuns. On that day, the celebrants, calling themselves “Doves,” released seven of the birds during rituals presided over by 15 priests and headed by a bishop.

Considered a progressive by the more conservative members of her community, Myrna had evolved a decidedly feminist perspective. And yet what struck me about those proceedings was that 15 Catholic priests, embodying patriarchal traditions, were giving their blessings to seven women. I have no doubt Myrna was aware of this ironic subtext. In her homily, she quoted Rilke, “Infinite dreams but finite deeds,” and referred to “a Steadfast Compassionate Mother God who knows where we are going even if we ourselves sometimes don’t.” In that reference to God as female was encapsulated the part of her voyage that most of the congregation’s other members would refuse to undertake, a voyage that harked back to the sacred iconography of pre-Hispanic times when Bathala, the Divine Principle, had no gender, and the first man, Malakas, and the first woman, Maganda, sprang forth from bamboo at the same time and as equals.

I never imagined my fun-loving ‘ate’ would one day opt for the life of a religious. Before becoming a nun, Myrna, never a ‘santa-santita,’ had already been working, had had a busy social life, had had suitors. One night, coming home from a party, she had an epiphany and knew she wanted to be a nun. As she prepared for bed, Myrna remembers listening to Frank Sinatra singing these lines on the radio: ‘The party’s over, it’s time to call it a day! They’ve burst your pretty balloon and taken the moon away. Now you must wake up…’ For some reason the ballad crystallized her feelings.

Her decision made my mother unhappy. Just six months before, joseph, one of my older brothers, had entered the Society of Jesus convinced of his calling to be a priest. Partly, my mother’s unhappiness stemmed from the fact that my sister didn’t quite know life yet, hadn’t explored its possibilities. Too, she and Joseph working in the secular world, had considerably lightened the economic burden of caring for the rest of us, for by then my mother had become the main breadwinner; my father, moored in a castle of discontent and bitterness, welcomed these defections to the Divine. In time, however, my mother accepted my siblings’ decision.

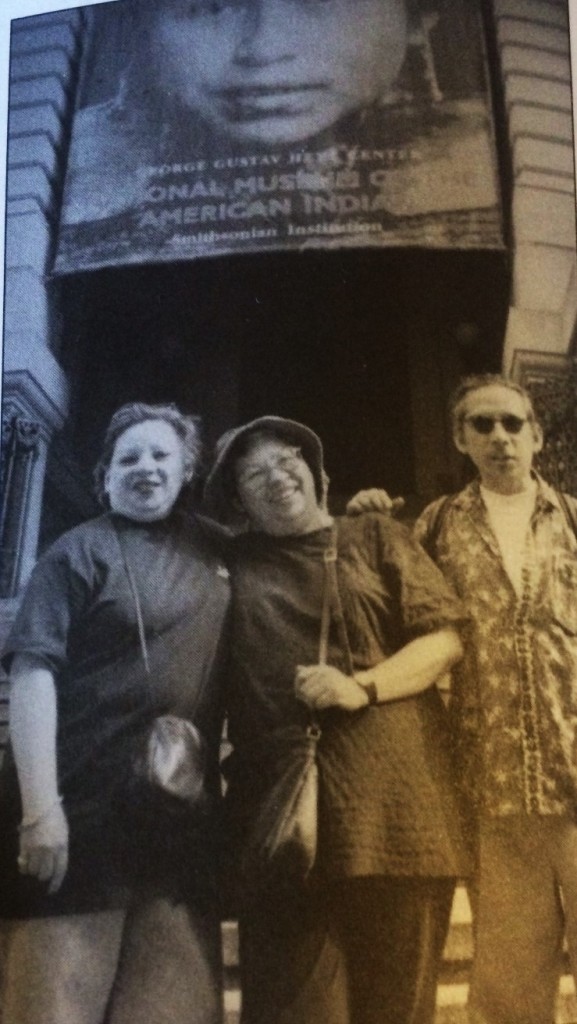

Myrna Francia (center) with siblings Luis and Judy at the National Museum of the American Indian in NYC, 1995.

Myrna’s experiences as a missionary in the Philippines’ remote rural south, then in the Indian state of Kerala, and her studies in Europe, made her see how, in a country as poor and beleaguered as the Philippines, asserting a communal bond with the less privileged was, to her, much more compelling than the traditional route of contemplative isolation. She once told me that living among the fisherfolk of Mati, Davao Oriental in Mindanao, for two years during the Marcos regime “saved me from being a dried-up prune of a nun.”

As an educated urbanite, she initially displayed a smug self-righteousness thinking she and the American missionaries based in Mindanao had true faith while the peasants only had superstitious beliefs. “My pompousness crumbled upon hearing their genuine faith reflections and their from-the-heart prayers. It was a real liberating experience.” Marcos had declared martial law in 1972, yet the intensity of these peasants’ faith when confronted with an emboldened military opened her eyes “to the deeper realities of my country, those whom I previously never knew nor appreciated as ‘bayani’ (heroes).”

Myrna remembered the courage of the people she worked with, such as Nang Vecing, a fisherman’s wife. “She was no coward whether facing priest or police. She said things as she saw them. Jailed by the local military unit, she declared: ‘Maybe the soldiers don’t know the gospel of Jesus and so they confuse Marx with Mark.’”

She remembered too a fisherman by the name of Noy Tonying who, tagged a radical, was also jailed, his fishing boat confiscated. Myrna described him as a “tiny flashlight penetrating the sea of darkness.” This metaphor occurred to her after an unforgettable experience of being with Tonying and some catechists at sea when their boat began to have engine trouble, putting them at the mercy of the waves. “I had a flashlight which helped to throw light, enough to fix the engine by and get us back to shore.”

I asked her if she felt she had taught the fisherfolk something. “Something for sure. But much much more I have learned from these ‘mayukmok’ (ordinary people). Through their unsung lives and unheralded deaths, they bring in the ‘ani,’ or harvest, of justice and peace.” The situation there had gotten worse, she pointed out, during the subsequent decade, with even more brutal militarization. “And how is Mindanao today?” she asked rhetorically. “Still bleeding. And its ‘mayukmok’ are still standing tall, honoring their faith in life even by their dying.”

This piece is excerpted from the writer’s book “Eye of the Fish,” published in 2001 by Kaya Press in New York. It is also one of the essays in the book “The Party’s Over: A Nun for Modern Times: The Story of Myrna H. Francia, ICM” edited by Lorna Kalaw Tirol.