Justice Scalia and me: A love story

By David Lat

Happy Valentine’s Day. I hope you are spending it with someone you love. I will share with you the tale of the great love of my youth: Justice Antonin Scalia.

Until last year, the happiest day of my life was when I found out I would be interviewing with Justice Scalia for a clerkship. I was living at the time in Portland, Oregon, working as a law clerk for Judge Diarmuid F. O’Scannlain of the Ninth Circuit. I learned the good news from Judge O’Scannlain, who was one of Justice Scalia’s “feeder judges” (a lower-court judge who regularly “fed” his clerks into coveted clerkships in the justice’s chambers). Judge O’Scannlain told me to call Justice Scalia’s secretary, Mary Ellen, to schedule an interview — which I did immediately, my hand trembling as it held the scrap of paper with the 202 phone number on it. The phone call lasted barely a minute, and I worried that perhaps I was too brusque (but I think it was simply that Mary Ellen was efficient).

After leaving Judge O’Scannlain’s chambers that day, I went for a run along the Portland waterfront. It was a sunny, clear day, the reward for enduring a rainy Oregon winter, and I ran as fast as I could. I felt invincible.

Why was I so elated? Partly because a Supreme Court clerkship is the shiniest brass ring for bright young lawyers, but partly because I had scored an interview with Justice Scalia in particular — my favorite member of SCOTUS by far, and my judicial idol.

As a conservative law student and then a young lawyer, I worshiped at the altar of Scalia. I treasured his book, “A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law,” and I referred to it frequently when analyzing legal issues. I’d often ask myself, “What would Justice Scalia do?”

I thrilled to Scalia opinions; sometimes reading them would give me chills. I loved his forceful dissent in Morrison v. Olson so much that I gave it a standing ovation — standing by myself in my New Haven apartment, wearing pajamas, at two o’clock in the morning.

That reading a judicial opinion caused me to pump my fists and clap my hands in the middle of the night like a crazy person is partly a reflection on my youthful nerdiness passion for ideas, and partly a testament to Justice Scalia’s greatness as a thinker and writer. Many law students and lawyers, especially those of us who are right of center, have similar memories about reading Scalia opinions; agree or disagree with him, “[t]here has never been a Supreme Court justice as much fun to read, debate, and learn from than Antonin Scalia,” in the words of Professor Adam Winkler.

I wish I could remember more about my interview with Justice Scalia. Truth be told, I was so nervous that the day passed by in a blur to me. I recall speaking to the justice for about half an hour in his office, perched on his sofa while he sat in a chair. Because I viewed him as a God-like figure, I thought he’d have a deep, booming voice, like movie or television depictions of God; his voice was higher and thinner than I expected. He was also physically more compact than I thought he’d be, as well as warmer and friendlier. We spent the first few minutes chatting about high school speech and debate. We shared in common the experience of debating for Jesuit all-boys high schools in New York City — for rival institutions, he for Xavier and I for Regis — and I suspect that my being a “Regis boy” helped me get the interview. (I listed Regis on my résumé when applying to Justice Scalia — on Judge O’Scannlain’s advice, if I’m remembering correctly.)

The justice and I then turned to discussion of substantive law. Unlike many other legal employers, who view an interview as basically chit-chat about one’s résumé, Justice Scalia liked to see how an applicant’s mind worked. We wound up debating Apprendi v. New Jersey, a Supreme Court decision issued earlier that year that called into question the binding nature of federal sentencing guidelines, based on a reading of the Sixth Amendment right to jury trial. I thought I knew the topic pretty well — I had taken a year-long seminar on federal sentencing and had written one of my two main law school papers on it — but Justice Scalia of course wiped his carpeted floor with me. He did it very kindly, I must say; I felt like we were just two minds working together in good faith to find the right answer to a problem (which was of course his answer, as Apprendi’s progeny established).

(Justice Scalia’s law clerks — who subjected me to a brutal, four-on-one, two-hour intellectual hazing after my meeting with the justice — were less kind, but that was their job. They played “bad cop” to Justice Scalia’s “good cop” in the clerkship interviewing process. And I’m glad they did; years later, I used my (somewhat traumatic) experience as fodder for my novel about the Supreme Court clerkship quest, “Supreme Ambitions.”)

Alas, my love for Justice Scalia turned out to be unrequited. A few weeks later, I received a rejection letter from him. It was a very gracious letter, but it still broke my heart. As I previously wrote, “Looking at my rejection letter was so deeply painful – sometimes it pushed me to the verge of tears – that I buried it in papers stashed in a bottom drawer.”

The years passed. The hurt subsided. I eventually harnessed my sadness and inferiority and turned it into a happy career as a legal blogger and journalist.

On the personal front, I came out of the closet (and realized that my ceaseless seeking after credentials was a manifestation of “best little boy in the world” syndrome). I found a man to love who loves me back. Last year, we got married — and our wedding day replaced the day I got a Scalia interview as the happiest day of my life.

Even though I found a new love (admittedly not Justice Scalia’s favorite kind of love), and even though I’m not as conservative today as I was in my youth, I still have a special place in my heart for Justice Scalia. I realize that statutory and constitutional interpretation are much more complex than I thought they were as a young law clerk and lawyer, but I still find much to admire in his theories of textualism and originalism. They’re not perfect theories; they’re just better than any of the alternatives.

Justice Scalia is sometimes depicted by critics on the left as cruel or mean, but that was never my sense of him. He was warm and welcoming when he interviewed me, he was gracious when he rejected me, and years later he even sent me a signed copy of his new book, “Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts,” for my birthday. My friends who clerked for or otherwise interacted with him also recall his charm, his generosity, and his warmth. And note, of course, his longtime friendship with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, with whom he almost always disagreed in the big-ticket cases.

Did Justice Scalia sometimes say intemperate or ill-considered things, whether to lawyers during oral argument or about colleagues in opinions? Absolutely. That’s because he cared passionately about the rule of law and the Constitution, and he was sometimes willing to offend people in the service of his ideals. Might it have backfired sometimes — alienating colleagues like Justice Anthony M. Kennedy or Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who held key “swing votes” in major cases, or turning off persuadable members of the public? Probably. One might say of Justice Scalia that when it came to the law and the Constitution, he occasionally “lov’d not wisely but too well,” to borrow the words of Shakespeare.

Justice Scalia was simultaneously the most God-like and the most human of all the justices. He was the most God-like because of his universalizing, totalizing, all-encompassing vision for the law — the vision that will make him, according to Justice Elena Kagan, a justice who will be remembered a century from now as “one of the most important, most historic figures on the Court.” Many of us will likely not see a greater justice in our lifetimes; I certainly haven’t yet in mine.

And Justice Scalia was also the most human, all too human — thanks precisely to his anger, his appetites, his laughter, and his love.

Requiescat in pace, Justice Scalia.

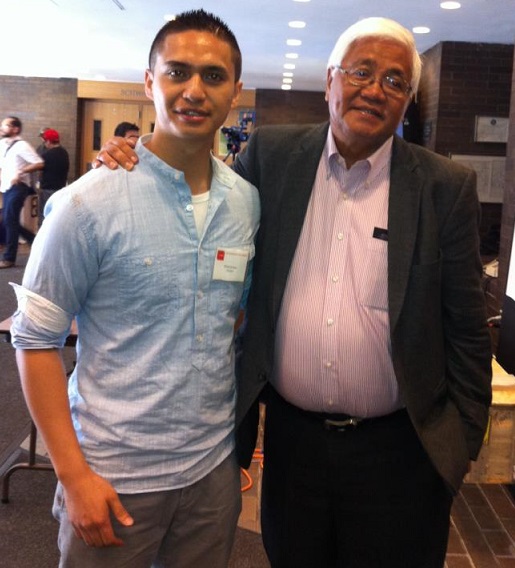

David Lat is a Filipino American lawyer, author and journalist. He is the founding editor of Above the Law legal blog, where this essay originally appeared on February 14, 2016. This essay is being republished with permission.

David Lat is a Filipino American lawyer, author and journalist. He is the founding editor of Above the Law legal blog, where this essay originally appeared on February 14, 2016. This essay is being republished with permission.