Dolly Fernandez: Growing up in a mixed-race family in anti-miscegenation era

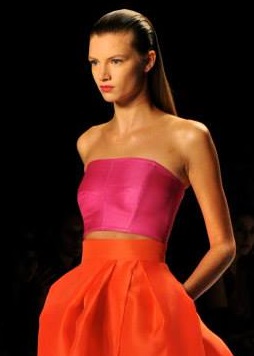

Pio Fernandez and Agnes Olsen; Dolly wins a beauty contest sponsored by a Filipino American organization in the 1960s. Photos: ‘Filipinos in New York City’

By Cristina DC Pastor

“It was a scandal, but it was also a happy marriage. They just had so much fun together.”

Dolores ‘Dolly’ Fernandez, the daughter of a Filipino valet and a Norwegian hat check girl, traveled back in time and shared fond memories of her parents’ stirring romance amid anti-miscegenation laws which criminalized interracial marriages in the 1930s to the ‘60s.

The statute was applied mostly on ‘Negro-white’ marriages, but hanged over the heads of Filipino pioneers – or ‘manongs’ — in California, who worked in plantations farms. Some of them married outside the U.S. yet they could not be seen in public with their wives because of fear of the law – which was repealed in 1967– and fear of public humiliation. By that time, the seeds of racial prejudice had been planted on the Filipino consciousness.

Dolly recalled growing up in a mixed-race family in New York City during this era where the prevailing attitude around the country was to frown on any union of different races. Filipinos were referred to as Malays. Her father, Pio Fernandez of Baybay, Leyte, and mother, Agnes Olsen, got married, made a home in Astoria, Queens and filled it with love, music, and laughter.

“My father was the personal valet of Gen. Douglas MacArthur,” she began when interviewed by The FilAm. “He traveled all over the world with him.”

After serving the general for five years, Pio came to the U.S. in the late 1920s and found work as a merchant marine. He worked as a seaman for many decades to the point that his family thought he would end up a bachelor. Until he met a beautiful hat check girl who worked at an elegant Manhattan restaurant.

“Every time he would land and came into port, he would go to this particular restaurant and say hello to this very pretty girl with red hair and blue eyes,” said Dolly laughing, “and my mother would say, what’s wrong with this man?”

“This man” was 50 years old, and Agnes was half his age.

“They just fell in love,” declared Dolly, their only child.

The marriage did not sit well with the Olsen family, who thought Agnes deserved someone better and not someone “who was old and who was brown.” Agnes’s Norwegian-Swedish family “disowned” her, and Pio learned to live with that. In the times she visited her parents in Brooklyn, only Agnes could enter the house. Pio and young Dolly, probably 4 or 5 at the time, waited in the car.

“Dad didn’t care that her family didn’t like him,” she said. “He would put her in a car, drive down Fort Hamilton Parkway so she could see her family in Brooklyn. Me and him would sit in car and wait. He would sing songs with me, like ‘Planting rice is never fun,’ we would play games, while mom visited her parents.”

That changed when her maternal grandfather saw his beautiful granddaughter and recognized the absurdity of a family unreasonably divided by race. “Until my grandfather said ‘This is wrong, this is a good man, we can’t do this anymore. We should not do this. I have a granddaughter.’ Everybody kissed. I remember it vividly, my grandfather hugging me, kissing me, squeezing me so hard. It was nice.”

Dolly remembered growing up in a fun and loving mixed-race family. “I didn’t know the difference. I didn’t know it was anything odd. Now people bring it up to me. Then, it was natural.”

Her mother quit her work with the restaurant and became a full-time housewife, which she loved. Her father, who was getting on in years, left the ship to work as a waiter at the famous Copacabana nightclub where the likes of Dean Martin and Sammy Davis performed.

“He would take me in the kitchen, and I could watch all the shows for free,” said Dolly. “We would bring home menus with signatures and autographs.”

She did not experience any racial affront growing up even though at the time, she had her father’s “very dark” skin. Her skin grew fairer over the years. Today, she has mestiza features, evidence of her Anglo-Asian roots.

“In school I was very smart, that’s probably why I was not treated badly,” she did. “I was always at the top, always getting 100. I never failed.”

Deep within, Dolly felt she did not fit in either side. Her mother’s Scandinavian family thought she was not too white, and the Filipino side felt she was not too brown. “I was an oddity,” she laughed.

It was also difficult, she quickly added. She grew up not knowing any Filipino kid because there was no one in the Queens public schools she attended. Her friends were mostly Irish, German, Italian and Greek children.

Beauty contests

But something she did made her closer to her father’s culture: She joined beauty contests and won many of them. She was crowned titles, such as Queen of the Filipino Social Club, and Miss Philippine-American 1968, and her parents were proud of her.

“I loved it,” recalled Dolly of joining beauty contests on the prodding of her parents. “I felt a sense of belonging. I felt camaraderie; I felt community. I felt a sense of family.”

After a while, she realized she was winning because her father sold rolls and rolls of tickets to his Filipino friends at the navy yard. “It’s about money. Not about beauty. That’s when it hit. I didn’t want to hurt his feelings so I made up excuses like I was busy with school.”

Dolly continued to remain engaged with the Filipino community even after her father died in 1980. Through divorce, widowhood and raising families, she was an enduring member of the Filipino American Human Services, Inc. for many years until funding issues forced its closure. She is currently treasurer of the Filipino American National Historical Society Metro NY Chapter. In yet another one of her cultural commitments, Dolly has joined My Barrio My Borough in a recent oral history project. She and other Queens residents told the stories of their lives as they wove strips of fabric on a loom. Dolly’s narrative is one of the richest, most poignant, punctuated by race, family drama, and political history.

Dolly shared how her house in Astoria has this crest, or coat of arms, representing both the Fernandez and Olsen families.

“Every time I leave the house I look at the crests and they remind me of who I am,” she said. “I am both Filipino and Scandinavian, and I identify more as Filipino. Being Filipino was a stronghold in my home.”

[…] Dolly Fernandez: Growing up in a love-filled, mixed-race family in the anti-miscegenation era […]

Great, thanks for sharing this article.Thanks Again.

“I really liked your article post.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…”

You have outstanding articles.