The FilAms of Silicon Valley: They are not all techies (Part 1)

By Harvey I. Barkin

SAN JOSE – “The story goes,” Edwin Torralba related, “when it was time to choose, the Philippines chose to have an Asian Institute of Management while India chose an Asian Institute of Technology.”

Edwin was a technical writer but when the permanent job became contractual and then dried out, he re-invented himself. He has been an election specialist for seven years now at the Registrar’s Office.

But like so many buyers, assembly operators, technicians and other former workers displaced by the high-tech bubble, he still follows the industry. The fascination is hard to get out of your system.

Edwin’s tale of the road not taken is also his personal story. He was plunging headlong into a sure-fire revenue generator when the road eventually forked: hardware or software? Unfortunately, he picked hardware. In almost no time his tech writing service folded.

He came to the U.S. in 1983, a couple of years before the personal computer was marketable and the Internet was only known to companies like IBM and Xerox and the military.

First tech writers were retired teachers

“When I came over, there was no technical writing position. Mostly retired or laid-off Caucasian teachers were the first tech writers. In fact, the high-tech companies can hire you off the streets if you can write!”

“In the early days of the semi-conductor industry, Filipinos who lacked in high school years didn’t have a problem. There was even a time when a high-tech worker without a degree just learned on the job.” And engineers who immigrated to America were checked out for their education, not their background.

Edwin’s entry into the U.S. was via inter-company transfer. American Micro System took Edwin from his HR management job in the Philippines to Santa Clara City. There was a shortage of engineers in the early 1980s. The company justified the need for Edwin because he had the communication skills and he can train personnel in the U.S.

Edwin revealed, “I’m a Philosophy graduate with no engineering background. But one of the qualifications of a successful tech writer is a quick learner. That’s what I was.”

“In those days, it was easy. Other Filipinos took Tourist or Business visa to come train in the U.S. for a week or a month then go back to their company in the Philippines. Some who got multiple-entry visa can easily come and go and even take care of their paperwork stateside. Their companies petitioned them.”

One notable Filipino-majority burn-in-board company was Dynavision, co-founded by Ernie Poblacion, Edwin said. Depending on the work load, they hired three shifts of mostly Filipino production workers. Most times, an operator can work one shift then walk a few blocks to the next shift at another fab house. Some assembly line workers, Filipinos or not, were able to afford their homes in San Jose this way.

Pays more than MacDonald’s

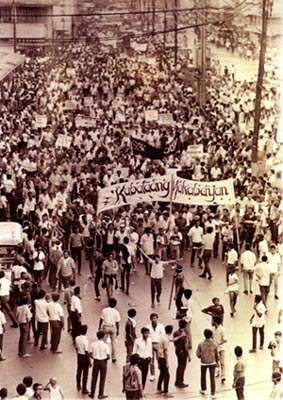

Edwin recalled, “Around 1980 to 1985, there were Filipinos working as assembly operators and technicians in places like VLSI Technologies, LSI Logic, AMI Semiconductor, Cygnetics, Motorola and Texas Instruments. Assembling the chips was labor-intensive, and manufacturing was 24 hours. There were usually three shifts. Filipino immigrants joined the assembly lines because the pay was better than MacDonald’s.”

There were some semiconductor companies already in the Philippines like Stanford Microsystems Inc. (at that time the chairman was Cristino Concepcion Jr.), Cygnetics Inc., National Semiconductor Corporation, Intel Corporation, Motorola, Texas Instruments, and Fairchild.

“There was an attempt to establish fab houses in the Philippines but it was not feasible. Fabrication requires a lot of water. A clean room environment and a lot of capital were also required. The process for wafers was also capital-intensive. So the main operations in the Philippines were mostly testing the die attach and testing the IC. Some of them are still in Pasig, Sucat and Bonifacio Food Terminal. Some are now in Baguio and Cebu. But most of them are in Metro Manila because of the bonded and abandoned warehouses.

Many fresh graduates in Manila were entry-level employees there. But their courses didn’t prepare them for semiconductor work. The best course would be Electric Communication Engineering. But it was rarely offered in Philippine schools at that time.

Harvey Barkin was a Senior Buyer then Tech Writer in Silicon Valley in the 1980s. He wrote book reviews for Small Press, Rhode Island, then Independent Publisher, Michigan, in the 1990s. He has contributed to many FilAm publications mostly in California. He received the Plaridel Award in 2013 for In-depth Investigative Reporting.

Next: Who is Dado Banatao?

The FilAm’s Investigative Reporting Project is made possible through the generous support of our readers and contributors including the following:

Consuelo Almonte

Melissa Alviar

Amauteurish.com

Bessie Badilla

Sheila Coronel

Joyce and Arman David

Menchu de Luna Sanchez

Kathleen Dijamco

Jen Furer

Marietta Geraldino

Dennis Josue

Lito Katigbak

Rich Kiamco

Monica Lunot-Kuker

Michael Nierva

Lisa Esperame Nohs

Cecilia Ochoa

Rene & Veana Pastor

John Rudolph

Roberto Villanueva

2 anonymous donors

[…] The FilAms of Silicon Valley: They are not all techies (Part 1) […]

[…] The FilAms of Silicon Valley: They are not all techies (Part 1) […]

I just want to say I really liked your blog. You really have great stories.

I just couldn’t leave your website. I really appreciated this article.