Balikbayan, murky, post-modern (Part 1)

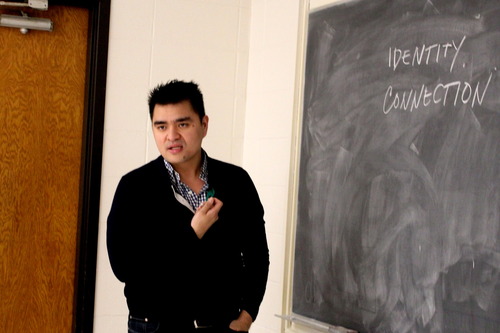

The author reading fiction at a writers summit held at the UST Center for Creative Writing and Literary Studies

My grandparents had come to visit us before my family left to spend a year in the Philippines in the late ‘70s, when I was 10 years old.

As pasalubong (I didn’t yet know the word), they brought two small clay models of what I suppose to be pre-Hispanic stoves. These objects reminded me of something I had seen in National Geographic. I thought we were going to live in huts in a primitive village, and when we flew off the following summer to live for 10 months with my mother’s family in Quezon City, I was completely shocked by the megapolis we came to inhabit. It was infinite with people, cars, motorcycles, a language I was only just beginning to understand, relatives of whom I was just learning the names. When I first came to know my ninang, I called her “Aunt Tita Bing,” as I did not realize the two words meant the same thing.

And it’s been a life of such mysteries, recognition, mistakes and learning, coming home to a place that may be at the center of our hearts and psyches (after all, we speak of our mothers), but sometimes we feel that perhaps it is also not quite ours. If we Filipino-Americans are fortunate enough to visit the Philippines, we can laugh or cry over the things we recognize and don’t. We are not foreigners, we’ve been challenged to balut before. We know of patis, we know that favorite curse involving one Spanish word and our mothers. Some of us speak Tagalog, some of us don’t, most of us at least understand some, or perhaps Ilokano.

As writers, we have likely read “Noli,” if we’re deeper in maybe Nolledo’s “But for the Lovers.” I myself have learned much from Filipino writers and intellectuals I met in New York, the second megalopolis I came to inhabit (I’m from East Lansing, Michigan, land of one high school and one small mall). But New York feels not-very-dense compared to Manila. I have been surprised more than once that this country, that is in many important ways the Motherland to me, does not feel entirely “third world,” as we might have learned from the West’s vision of our country, our double-consciousness (though of course it is in the most troubling senses, the overwhelming economic struggle). Something about the infinite malls feels Brave New World to an American, its controlled atmosphere, the future when all is inside, brisk and clean and organized. And there are gadgets that moneyed people have, little flashing objects that bring Internet through impenetrable walls, apps that predict the pace of traffic (oh the traffic!) and the density of human life. I will never hear anyone complain about the claustrophobia of New York anymore without knowing they must be naïve. And all of this, all of these lessons, mysteriousness, bifurcation of nations and identity, I find more complicated by the fact that I am biracial. More on that later.

Rain and Writers: RV Escatron, Lawrence Ypil, Ricco Siasoco, Sarah Gambito, Nerissa Balce, Fidelito Cortes and F Jordan Carnice. (Photo courtesy of F Jordan Carnice)

And so, it is with a great deal of emotion, promise, and curiosity, that I found myself fortunate enough to join a group of Filipino-American writers who visited the Philippines in July. Among us were: M. Evelina Galang of Miami, Sarah Gambito, RA Villanueva and Ricco Siasoco of New York. Fidelito Cortes and Nerissa Balce, also of New York had been spending a few months in Dumaguete, and they joined us for our events, and most importantly, the epic socializing that is one of the great joys of Filipino life. R. Zamora Linmark, world traveler, with whom we have broken bread, no, spooned up rice, in NYC, facilitated an event at UST.

Coming from New York, with its careerists, its brisk walkers, and curt get-on-with-it daily interactions (and don’t get me wrong, I love New York), the kindness, hostmanship, the conversation, lessons, festivities, the adobo and joyous puns with which we were received by our families, colleagues and friends newly met, were particularly moving. We had been discussing the trip for almost three years, and in the months before we left, as it all became real, I was very surprised by, and grateful for, how accommodating the universities we visited were. I had written to ask if we might set up a reading: each school not only did so, they did tremendous jobs of bringing out the audience. I had expected small gatherings, but we had large turnouts. Writers and scholars chatted with us formally and informally. We got to ask about the local literary scenes.

The organizers, led by Mark Anthony Cayanan and Daniel Olivan at Ateneo, Jing Hidalgo and Ralph Semino Galan at UST, Ian Casocot at Silliman who included us in the university’s second Literatura conference, and Jeremy Cha and Dinah Roma at De La Salle made very special events happen.

Each reading had, of course, its memorable moments. All of us read at Ateneo, the crowd, mostly students, a mix of graduate and undergraduate, it seemed, was young and hip. After our readings, Daniel Olivan asked us to talk about our notion of home in relation to the Philippines.

Three of us answered. I loved the question because it helped me process and articulate some of the particularities of identity with which I have always grappled. I got to say that it is complicated, that the Philippines does feel like home (notice the italics reflect an insecurity), that it meant a lot to me that my cousin’s girlfriend posted, “Welcome home,” on my Facebook page. I was grateful to be told the nation belongs to me, in some way, too, at the same time I must acknowledge that this is a complex matter, troubled by a colonial history that rewards, the “mestizo” class. This is a practice, that as a person of conscience, I am uncomfortable with, though I am human and I won’t deny my weaknesses must show in the day to day. RA Villanueva used the word “permission,” to describe our longings, a very apt articulation of our relationship to parents’ homeland, we seek permission. It is a cliché of American race thinking that the “tragic mulatto,” is not a part of any community, but there is some truth in being Other in the United States, and feeling anxious in some ways, though also privileged, in the Philippines.

I should say the incredibly warm and gracious Filipino culture alleviates much, perhaps most, of that anxiety. I was surprised by Fidelito Cortes’ answer to the question of home. He said he is not a Filipino-American. He lives in the U.S., and has for many years, but does not claim the hyphenated identity that many of our friends who have immigrated do. This foregrounded that our experiences are quite varied, our decisions about complicated identities are quite varied because there are so many ways we might possibly think about our place in the world when our position is new or unique within history.

NEXT: Being ‘tisay’ and feeling conspicuous in the Philippines

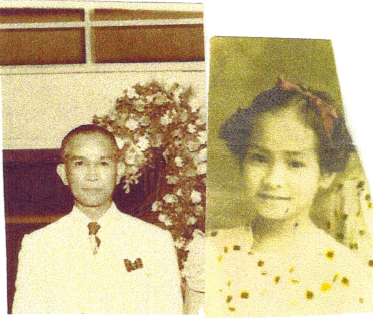

Lara Stapleton was born and raised in East Lansing, Michigan, and also lived for some time in Quezon City, whence her mother hails. She is the author of “The Lowest Blue Flame Before Nothing” (Aunt Lute 98) and the co-editor of “The Thirdest World” (Factory School 2007) and “Juncture” (Soft Skull 2003). A writer of poetry, prose, and screen work, New York City is her home. Lara’s grandmother, Adelaida Bendaña came as a Barbour scholar from the Philippines in the ‘30s, and enticed her husband Barker Brown, to spend the rest of his life in the Philippines. He was POW under the Japanese at Santo Tomas, and had great grandchildren when he died in the Philippines. Only one of their children, Alicia, immigrated to Michigan, from where her father hailed, and where she met Lara’s father James Stapleton at Michigan State.