Nanny juggles playdates, Pampers and paint brushes

By Cielo Buenaventura

Even in a city where many people juggle two or more jobs, Mona Lunot has an unusually doubleheaded calling card. She is a nanny who is also an artist.

By day she cares of one family’s 16-month-old baby and another family’s 3 1/2 old toddler. She also has a cleaning job in a third home, on Park Avenue.

At night, or at least on nights when she can summon the energy after a full day of playdates, feedings and cleaning, she sets up brush and easel in her small studio apartment in the Bronx, and paints, for long hours — on weekends, till the break of dawn.

She calls painting her therapy.

“It’s a way of easing my heart and mind from isolation from my family and friends as an overseas Filipino worker,” she said.

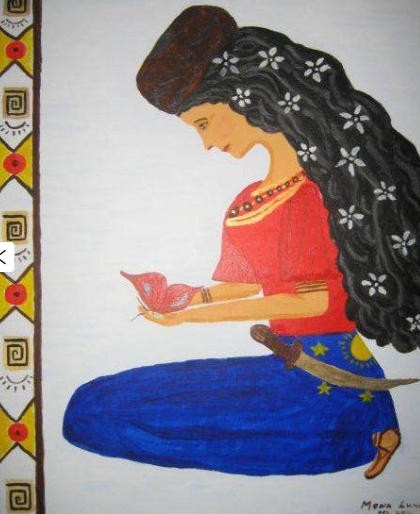

Her colors are bright, her images often symbolic, her representations direct and bold. And the subjects are often heartfelt.

Her subjects are mostly other Filipino migrant women who have joined the exodus abroad to earn money to send to their families back home. Many of them are college-educated – teachers, clerks and factory workers – who come here as domestic workers hoping that babysitting and cleaning houses are just steppingstones to better jobs. But often disappointment meets them at the first stop.

For Mona, the transition was rough. A former electronics company worker in the Philippines, when she came to the U.S. in 2000 her first job as a live-in housekeeper for a diplomat was literally full time — no days off. “I worked for seven days a week and was paid $250 a month,” she said. She toughed it out for eight months then “escaped in the middle of the night.”

From there, she has made the rounds of Park Avenue’s gilded high-rises in various jobs: housekeeper, companion/cook, house manager and server during private parties of wealthy people. Some of the people she worked for were kind, but others did not hesitate to put her in her place. She still remembers the time when one of her employers gave her a slice of pizza and “threw it on the kitchen table without a plate.”

She quickly learned that her story was not unique. Domestic workers are easy targets of exploitation and abuse from employers. Often part of an underground economy, they are largely invisible and easily replaceable. But rather than give in to despair and helplessness, Mona found a way to tell her story – and those of other Filipino nannies.

One way was to put old skills to good use. She had been a union officer during her 14 years as a machine operator for Temic Electronics in the Philippines. So, she thought, why not organize here? Before long she headed a domestic workers’ group in New York and spoke out at rallies and hearings demanding legal protections for migrant workers.

But she also gave voice to the plight of nannies through her newfound passion for art.

At first, to ease the pain of homesickness as she sat in her small rooming house after work, she wrote long poems in Tagalog about the struggles in New York. Then, five years after arriving in the U.S., she started painting.

She learned to paint by reading art books and visiting museums, although she had a brief, memorable exposure to art as a child. Her father, Leonido Lunot, painted as a hobby. “I saw my father painting when I was very young,” she recounted. “He loved to paint but because we were poor he could not afford to buy the necessary supplies.”

Her father passed away when she was 17, and it grates on her that he was not able to achieve his dreams as an artist. Mona, an only child, was a college freshman at San Sebastian College-Recoletos in her hometown of Cavite when her father died.

“Because of our financial issues, I decided to work to support myself and my mother,” she said. She found a job at the electronics company and stayed for 14 years until she was laid off after a strike.

She never knew she had in her to be an artist, she said. “Basta isang araw na lang para akong hinihila,” (“One day, I felt its powerful pull.”)

She wants to devote her art to people like her. “I want to give justice and value to women’s significant contributions in society, especially the domestic workers,” she said. “The sad thing is we are being marginalized and abused.”

She got a chance at the spotlight last March when she was selected as one of 12 artists for the show “Arrivals/Departures: Women’s Experience of Migration Under Globalization,” at Project Reach in Manhattan. Organized by the Guatemalan-Mexican artist Leilani Montes and the Filipino novelist Ninotchka Rosca, the exhibition, sponsored by the feminist group AF3IRM, brought together women artists from various ethnic groups to explore the theme: “migration is not just a legal, labor or policy issue but a life-changing experience for the immigrants and their children.”

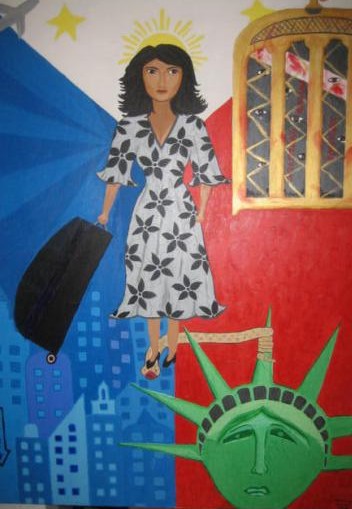

Mona’s painting “Maleta” (“Suitcase”), she said, “is my story, and it’s also the story of all Filipino women who migrate or are forced to migrate to support their family.”

The piece, rendered in acrylic, features a Filipino woman in her Sunday best, lugging a suitcase, her face reflecting both hope and apprehension; around her are skyscrapers, Lady Liberty, the Filipino flag and sad, tortured faces peering behind bars. A snake, whose tail is coiled on Lady Liberty’s crown, seems to say, “Beware, this journey is fraught with danger.” But the woman stamps on the snake’s head.

Mona invited one of her current employers, Lynne Klyde, whose husband is a prominent Manhattan doctor. “Nagulat sila, hindi nila alam na nagpipinta ako,” she said. (“They were surprised. They didn’t know that I paint.”) Before the show they paid $500 for “Babaeng Mandirigma” (“Woman Warrior”), a 16 by 22 paean to Gabriela Silang, the first Filipino woman to lead an uprising against the Spanish colonialists.

One work this artist deeply values, “Temic Strike in Canvas,” depicts the workers’ strike at the electronics company that led to her and her fellow strikers’ dismissal. Arnedo Valera, a human rights lawyer in Virginia, ordered the painting, Mona said. She asked for a donation and so far he has sent nothing, she added. And he would not respond to e-mails asking why.

The long solitary nights of creating art is beginning to pay off. Most of her early works were sold to relatives and friends. These days she is finishing a piece commissioned by another former employer, a portrait of an 8-year-old child whom she used to baby-sit.

“I have several orders but I can’t sustain them because people want the same paintings,’’ she said. “I don’t really like repeating my works.”

Although she is not ready to give up her day job, she looks to the day when she can fully pursue her art.

“I’m happy that I was able to fulfill my late father’s dream,” she said. “I will not stop doing this to give honor to my father and our country.”

Mona Lunot’s portfolio of paintings can be found here.

Journalist Cielo Buenaventura lives in Manhattan with her husband and their 10-year-old son.