An invitation to a fellowship: Rebranding ‘balikbayan,’ what it means and what it can be

The author and founder of the Kaya Collaborative fellowship that seeks to immerse young leaders in Philippine social conditions.

Having spent equal halves of my life in the Philippines and in the United States, I never know whether to call myself a Filipino American or an American Filipino – which word defines the other, which adjective colors the essence.

Since my arrival in the U.S. at the age of 11, my Philippine narrative has been an arc of detachment and devaluation and in the end, rediscovery. A trip back home, a Tagalog class, and an independent course on FilAm culture with Brown University’s Filipino Alliance were a few of the guideposts that brought me back to an empowered idea of what “Filipino” really meant. And since then, a certain word has held a stubborn charm for me, a strange resonance that straddled the line between identity and aspiration: “Balikbayan.”

“Balik” as in back. “Bayan” as in nation. All together: Returnee. Repatriate.

Balikbayan, as in giant balikbayan boxes that would sit in the corner of my house, filling up over the length of a month with towels, DVDs, processed meat, and preserved pieces of my mother’s heart before being taped up and shipped to our extended family across the world.

Balikbayan, as in the balikbayan line at the airport, two years ago when I finally returned to the country where I spent the first half of my life, a trip that left me both transformed and unfulfilled.

Balikbayan, as in balikbayan remittances and donations that make up for 10 percent of Filipino GDP, from the 10 percent of the global Filipino population that has been driven out of our homeland by the lack of local opportunities for a secure and stable life. In 2011, this financial flow was 10 times foreign direct investment and about 100 times official development assistance received by the Philippines in the same year.

In the words of the Filipino Reporter: “The Filipino dream, to put it succinctly, is to leave the Philippines.” These transnational transactions are our little tokens of solidarity that say, no, we haven’t forgotten. Yet these remittances and donations almost always go towards immediate consumption or immediate relief, and never towards sustainable development and social change. Never towards tackling the same social, environmental, and economic causes that uprooted us so forcefully.

We’ve seen that it’s not for lack of caring. The diaspora is already organized tightly in communities that are built around the idea of a shared homeland – communities that already care, however abstractly, about a brighter tomorrow for the Philippine archipelago. But from a distance, it’s hard to guess the specific needs and the most promising models of change to rally around – much less begin to engage, build relationships, and exercise our imaginations about where we might best fit.

Dr. Jay Gonzalez, Philippine Studies Professor at the University of San Francisco, ends his book on “Diaspora Diplomacy” with a quote from Gandhi: “In a gentle way, you can shake the world.”

The connectivity of our migrant communities means that all it takes is the right nudge – a gentle shake – and the right informed message with the right resonance can very quickly echo down to tens of thousands of interested ears. A pronounced call to action can spark a powerful fire.

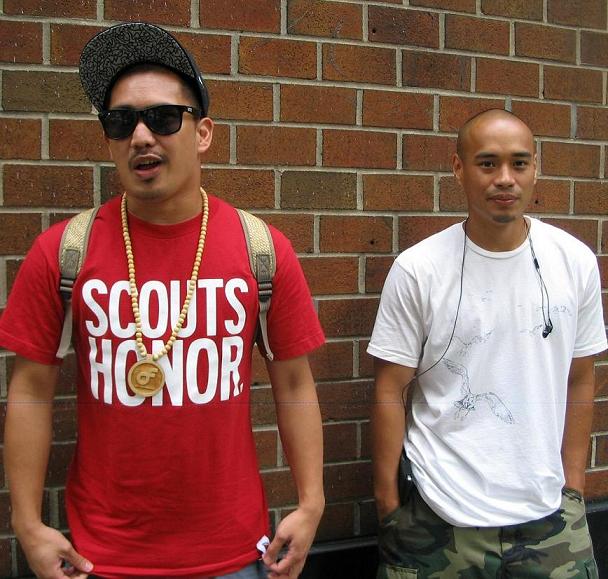

Brown University’s Filipino Alliance, where the concept of Kaya Collaborative was the subject of endless conversations. Dan Zhang Photography

For the summer of 2014, we at the Kaya Collaborative are recruiting the next group of transnational leaders to transform these communities that care into communities that care effectively – that care strategically – that invest their money, effort, attention, and creativity in new systems and solutions that last. Our fellowship program will place 12 emerging leaders (undergraduates and recent grads) in the Filipino diaspora into high-impact internships with our 12 social venture partners: game changing organizations that have made a commitment to tackling systems of injustice, inequality, and poverty in the Philippines.

A sneak preview of these internships:

• fundraising and stakeholder engagement with Ashoka Philippines, part of the largest global network of social entrepreneurs;

• social impact measurement with Rags2Riches, a “stylish social statement” that provides sustainable employment and training to over 800 artisan women;

• a rebranding campaign with Gifts & Graces, a fair trade organization that has worked to build capacity in, provide market access to, and raise the livelihoods of marginalized Philippine communities;

• and international marketing strategy with Route +63 Travels, an organization that promotes environmental responsibility and local development through tourism.

Fellows will also spend a day of each week collaborating to design the Kaya Compass: an online platform that will connect resources in the diaspora to social efforts in the Philippines. Our aim, in the end, is to develop agents of exchange: informed and inspired leaders who will activate their own overseas networks as allies and advocates to homegrown social change initiatives. Leaders who can shake their communities into active motion.

In the end, we want to redefine balikbayan: a word that has come, too often, to mean superficial if not purely symbolic return. We want to rewrite the unrequited love story of a homeland and its wayward sons and daughters. More than anything, we want to build towards a Philippine nation that is now fueled by the scattering that once crippled it – and a diaspora that finds strength, energy, and empowerment in the difficult liminality, the wicked in-between-ness, that has marked so much of our lives.

Dumaguete-born Rexy Josh Dorado is an Economics senior at Brown University. He is the founder of the Kaya Collaborative, a 10-week fellowship program that immerses young leaders from the Filipino diaspora in the Philippine social impact sector. Apply to be a fellow by February 10th.

[…] Read the whole article here. […]