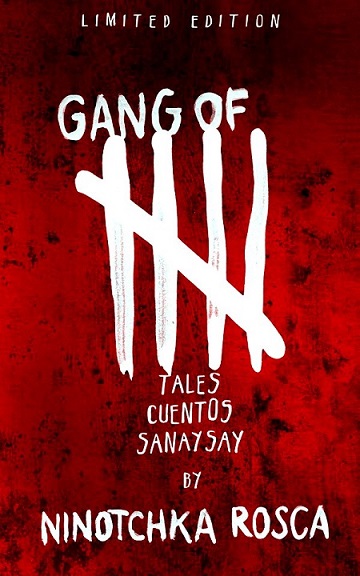

High five for Ninotchka Rosca’s ‘sanaysay’ anthology

While awaiting the international availability of Amazon’s Kindle Paperwhite, I placed some orders for a number of dead-tree editions – which also ran into unexpected delays. Meanwhile a packet arrived in the mail, containing a slim volume titled “Gang of 5: Tales, Cuentos, Sanaysay.” The author, Ninotchka Rosca, was someone I’d never met in person, although anyone with even a remote association with progressive literary circles in the Philippines would have heard her name sooner or later.

My personal regret is my failure in going beyond the opening pages of her first novel, “State of War” – I was then preparing for overseas graduate studies and ran out of time to read all the then more recent Filipiniana (mostly eventually damaged by the elements) in my collection. After having made the author’s acquaintance on a social network, I recognized certain qualities I’d grown familiar with from an earlier generation of activist authors, with whom I once hung out as a way of furthering my unsentimental education. Assertive, impatient with detractors, firm in her convictions, unsparingly self-critical, she would nevertheless surprise everyone with a graciousness that could only come from a first-hand familiarity with people-oriented service – from gestures as casual as sharing pictures (of her home, or her past) that made her happy, to helping an infirm neighbor abandoned by everyone else, to offering assistance to anyone devastated by natural calamity.

My “Gang of 5” copy will never leave my personal book shelf, mainly because of the author’s signature affixed to a handwritten quotation from Conrad Aiken – and also because of the text, “Limited Edition,” affixed above the title. In an exchange, Rosca said that the book will be available to a general readership by mid-year, and however one cuts the argument, it would be a major loss for readers of Philippine literature if it weren’t. For this, out of all the several anthologies of English-language Pinoy short fiction ever put out, will satisfactorily serve as the all-purpose single-volume introduction to local writing that anyone will ever need. None of the five pieces is less than inspired, each one represents a writing challenge distinct from the rest, and everything builds up to the larger anticipation of greater pleasures awaiting in the output of other Filipino authors – final proof of Rosca’s generosity of spirit in honoring her colleagues by providing evidence of how equal they are, as she is, to the challenge of literary excellence.

The book, as far as I can surmise from her social-network postings, was another of her selfless exercises in pursuit of a worthy crusade: it was intended as a giveaway for donors to the Mariposa Center for Change’s Stand with Grace Campaign, a so-far successful effort to prevent a corrupt and abusive congressman from forcing his mistress, who had sought asylum in the U.S., to return to his overeager clutches. Such a cause-oriented origin should not mislead the reader into expecting a series of feminist philippics; rather, the pieces are feminist in the best updated sense, some of them even abandoning the literal prescription of center-positioning a lead female character, and in one case even revealing an otherwise strong and politicized woman as a villain – a lesson well-learned from the never-ending “positive images” debates of whether Others should always be depicted as virtuous, unblemished, normative, wholesome, victims-but-never-victimizers, etc.

In fact one can just as well imagine a scenario where an enterprising publisher announces an extensive search for women’s writing in diverse genres, selecting the best entries submitted, and discovering too late that they had all been written by the same author. The collection opens with an account of the musings of a murderously inclined male sociopath, an achievement noteworthy if only for its success in comprehending the morbid mind, without recourse to the generic solutions of depicting the character as evil or abnormal; the story’s ultimate source of terror lies in how such a person emerges as normal, even respected, in the Third-World milieu where he operates. The collection then shifts gears – another country, another gender – and provides a feel-good (in the well-earned sense, for which my word will have to suffice for now) tale of what it means to be a Filipina within an imagined community, even among people who have precisely nothing else but their imagination to follow-through this exquisitely complex construct.

Rosca maintains the central story, “The Neighborhood,” as a link to her past and future as story-teller. It comes from her earlier highly acclaimed anthology “The Monsoon Collection” (which I also have not read, to my continuing chagrin). Here she orchestrates the interactions of one of the metropolis’s several slum neighborhoods, a colony within a colony; a possibly magic-realist event closes what is necessarily an open-ended account, so it makes perfect sense that the central character’s narrative will be continued, per Rosca’s declaration, in her forthcoming novel, “The Synchrony Tree” (whose excerpts she has posted on her blog Lily Pad, a pun on the Filipino expression “about to fly, or take off”). The last two pieces focus on women’s heartbreak, one a semi-nouvelle à clef seemingly based on a famous Philippine multimedia pop star’s self-exile in the U.S., the other an autobiographical-sounding account of a mother’s abandonment of her helpless, oppressed daughter. Rosca refuses the facile options of resorting to victimological formulations of these characters’ respective plights; the reader is assured of her sympathy precisely because of her willingness to cast a cool, almost clinical eye on the inner conflicts of these personae, familiar from the stock repertory of soap fictions yet unnervingly represented with flesh-and-blood tangibility in these texts.

Rosca recalled how Julie de Lima, wife of the founder of the Communist Party of the Philippines, once remarked that “Only Ninotchka can render Joma [Sison] speechless.” The occasion was a public exchange on the use of English as a medium for expressing the ideas and sentiments of Filipinos, with Sison asserting the standard nationalist line that only a native language will fulfill the challenge of depicting, say, a slum child’s innermost concerns. Rosca, by her own account, maintained that “language – any language – [is] a malleable tool, per the writer’s skill. I then asked him whether reading Mao Zedong, [who came from] a Chinese peasant family, in English translation implied a loss in the thoughts of the revolutionary leader…. The question is why we accept reading scientific, philosophical, or political tracts in a foreign language and demand that literature restrict itself to a first-level reality.” The incident reveals the little-known willingness of Sison in welcoming adversarial discussions, but it also cost Rosca the respect of some of his more fanatical followers.

“Gang of 5” is, among many other things, elegant proof of her defiant stance regarding the utility of the language she happened to have at her command. Its achievements would have needed no further justification beyond the serendipity of reaching a wide readership, but Rosca typically allowed it to shoulder a wide range of objectives – from assisting a battered woman, to embodying her convictions on language, even serving as a conduit in her once-and-future fiction projects – and like all major works of literature (even the shortest ones), the collection itself abides. Somewhere there’s a lesson for the country’s political and economic leaders, if they could find enough time and humility to draw inspiration from a few dozen pages of wondrously well-wrought prose.

Joel David is associate professor for Cultural Studies at Inha University in Incheon, Korea. He is the author of a number of books on Philippine cinema and was founding director of the University of the Philippines Film Institute.

GUERRERO YEE LLP. Trust our award-winning law firm with your immigration case.

GUERRERO YEE LLP. Trust our award-winning law firm with your immigration case.