How Mama reinvented herself in America (Part 2)

By Randy Gener

Eventually times got harder. It became more difficult to find work in the Philippines. Cleo had no choice but to disappear for longer periods of time. One reason she felt compelled to come to America was that in the late 1970s, she had conducted a long search for her U.S. father via her correspondences with his friends at the Veteran Administration office. When she first came to New York City, she did in fact locate her father in New Jersey — except that he spurned her again. He denied that he fathered any child in Bacolod City.

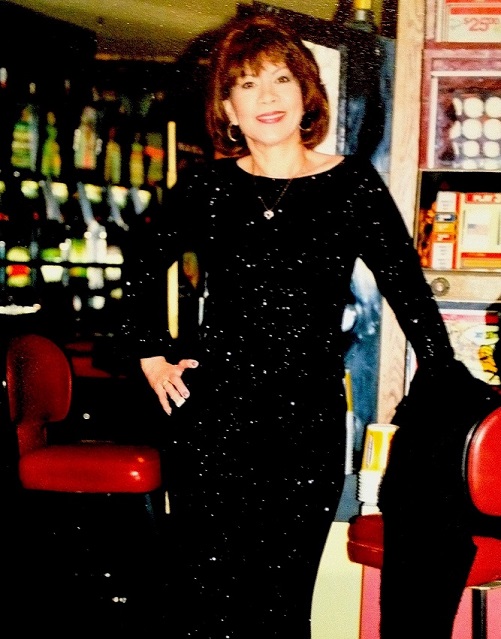

Prior to coming to America, Cleo had lived many lives. She had known pain, poverty, heartbreak, abandonment and love. She had become ferocious about rescuing her children from dire straits. Fighting for legitimacy, she demanded that all of her children become naturalized U.S. citizens. She married a decorated Vietnam War veteran and worked as a cocktail waitress for 18 years at the Club Cal Neva. By the time she settled in Reno, Cleo was about 38 years old, proving that anyone can reinvent his or her life at any age. Through the force of will, beauty, wit, courage and personality, Cleo created a new family in America.

On March 2009, the Philippine Consulate General in New York hosted a huge celebration. My Mom was the secret guest of honor. The heads of the English and theater departments of Cornell, Princeton and Yale Universities had chosen me to be that year’s winner of the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism. The party was supposed to be an award presentation.

I had a different agenda. That beautiful evening needed to be a tribute to Mom. I asked my dear musical performer/friends to sing an uplifting musical medley that would in effect serenade my Mom.

She arrived at the Philippine Center wearing a shiny gold suit and a dazzling smile. She led a small entourage of relatives and close friends who live in New York. For a week she stayed at my apartment and saw our daily preparations for the event, but we offered no clue that I had planned to specifically call her out from the audience and ask that she make her presence known.

In my speech I confessed that for decades Mom had hectored me about becoming a U.S. citizen. I resisted. Growing up I was exposed to an intense Philippine nationalism buoyed by anti-Marcos sentiment. “My greatest fear was that I would become a citizen of our former colonial master,” I said. I eventually changed my mind when Mom convinced me that the U.S. government had become more restrictive to immigrants after the Sept. 11 tragedy.

Now, a specific condition of winning the Nathan Award is that the recipient must be a U.S. citizen. A few months before I received a phone call from the Princeton University judge who sought for verification. “I don’t want to seem like Homeland Security, but I need to know if you are indeed a U.S. citizen because you are a finalist,” he said.

Looking directly at Mom in the front row, I reminded her that she was the first person I phoned when I had officially been named the winner.

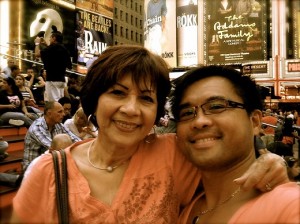

I continued: “So I brought you all here under false pretenses. You think you are here to honor me, but tonight is not about me. This evening is a vindication of my Mom’s life work. Tonight is a validation of my Mom’s achievements, which have made all of this possible. Since the New York Times reported that I was this year’s Nathan Award winner, people would say, ‘Much deserved.’ No, not really — I beg to differ. You are all here tonight to meet the woman who is so much more deserving than I am. Mama, you deserve recognition for all the years you worked two jobs, often cleaning other people’s houses in America, so that you can send money back home to the Philippines. Mama, you deserve to be honored for all the backbreaking years you worked serving drinks in the casinos so that you can send your children to school. You deserve praise for the sacrifices and hardships you had endured as an overseas Filipino. And you are right, Mama. You were right to annoy and hector me — to insist that I should become a naturalized American citizen. I am sorry for being angry at the time. This is the proof. You are absolutely right, Mama. This speech, this honor, this party, this award, this evening — this is a song for you.”“Yes!” Mom shouted in affirmation. “Tama ka! You speak the truth!” The audience laughed. Mom surprised us with the ferocity of her response. Of course I had to make up for it later by taking her to a Broadway musical that would leave her happy and giddy, but on that memorable night she could not stop crying.

Randy Gener is the Nathan Award–winning editor, writer and artist in New York City. He is the dramaturge of “Noli Me Tangere: The Opera” and the organizer/curator of Filipino Mundo-NYC, a MeetUp group of young professionals and visual/performing artists.

Mr. Randy Gener, so glad to have read your article about the time and life of your beloved Mother in the Philippine and in the United States. It is a very story inspiring, indeed.

M. Matthews: Thank you so much for reading my story. She had so many facets. Her story had not yet been told, and I hope to tell it correctly. We love her very much and I miss her so.

Thank you. I was deeply touched by this article Mr. Gener and reminded me of my mother. Kudos to you and your Mom must be all-smiles in heaven.

[…] How Mama reinvented herself in America (Part 2) […]