Art historian Nina Capistrano-Baker: Romancing the gold

By Cristina DC PastorCurating Asia Society’s massive, $1.2 million Philippine Gold Exhibit and troubleshooting all the big and small details could be intimidating. Not to art historian Dr. Florina ‘Nina’ Capistrano-Baker.

Her demeanor when we met over coffee was one of excitement, exhaustion, with an element of apprehension.

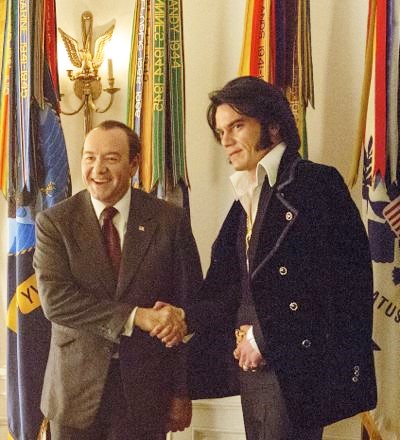

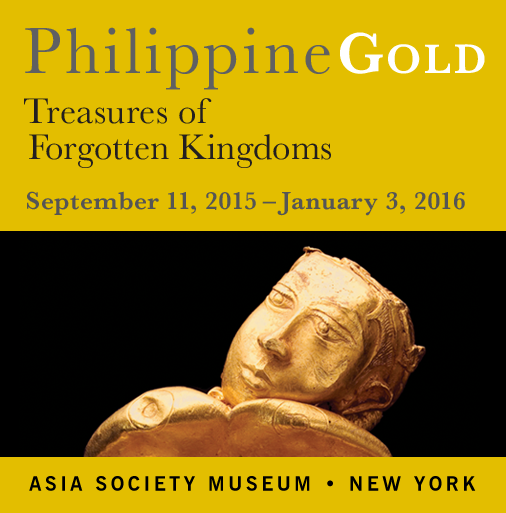

There is reason to be anxious about the upcoming exhibit on September 11 (to run until January 3, 2016). It will be the first time more than 100 pieces of pre-colonial gold artifacts will be on the road and transported outside of the Philippines. Concerns about damage and security are understandably high.

“To bring the gold to New York is a major commitment, a big risk,” she said. “Of course I’m anxious.”

Also highly charged and inspired. For the next four months, the entire Asia Society on Fifth Avenue will fly the Philippine colors. Organizers are hoping that Filipino Americans across the country will visit “Philippine Gold: Treasures of Forgotten Kingdoms” to view this unique collection, evidence of the craftsmanship and artistry of pre-colonial Filipinos.

“They only have three floors, and we’re in all of them,” Nina said sounding pleased.

The main exhibit will be held on the second floor. All floors will have an activity that supports it. The ground floor will have a pop-up store of Philippine products carefully selected by foremost Manhattan jewelry designer Federico de Vera. The third floor will be the venue of a video exhibit showing contemporary Filipino artists.

“Right now they’re painting all the walls,” she said.

Nina’s involvement with the gold collection began 15 years ago, long before art benefactor Doris Magsaysay-Ho of Asia Society Manila championed the New York exhibition and pitched it to New York CEO and philanthropist Loida Nicolas Lewis last year. It has been on a long, painstaking and somewhat intimate journey, and it’s all chronicled in the 2011 book “Philippine Ancestral Gold,” published by the Ayala Foundation and National University of Singapore Press.

What is likely left unmentioned is how Nina, the youngest daughter of a mining engineer, used in her scholarly research the maps of Philippine regions rich in gold deposits her father had surveyed in the 1950s. Gold was believed to be in abundance then in areas now known as Butuan, Eastern Visayas, Mindoro, and Surigao. The people created belts, necklaces, masks, rings, leg ornaments, even ceremonial weapons, and wore these gold objects in rituals and celebration and to establish their rank in society.

“I’m so sad,” shared Nina when interviewed by The FilAm. “He didn’t live long enough to see me do the gold exhibit.”

Part of the exhibit are 10th to 13th century objects such as (from top) ear ornaments, a goblet and belt buckles. Photos: Asia Society

Pablo Capistrano was chief metallurgist and mining board examiner at the Bureau of Mines, as well as head of the Geology Department. He was one of the country’s first 12 mining engineers who graduated from the Mapua Institute of Technology, the group earning the monicker Mining’s Dirty Dozen. He later studied metallurgy in the U.S.

She continued, “After the war, the U.S. government commissioned a survey. He was the last one to survey the gold and silver mines after World War II when all the records were lost. The map of gold deposits that we published in the 2011 gold book was based on my father’s survey map of gold and silver mines in the archives of the Philippine Bureau of Mines.”

‘Accidental’ art historian

Nina, the youngest of seven children – four girls and two boys – did not plan on being an art historian.

“I wanted to be a Psychology major,” she began. When advised she had to get a Ph.D. to have a successful career as a psychologist, she decided to take up Humanities instead, to acquire a liberal arts foundation for a subsequent MBA.

“I was thinking I’m not gonna do a Ph.D. Why would I want to be a nerd?”

A Humanities major in University of the Philippines where she graduated cum laude, she met renowned art historian and curator Rod Paras-Perez who was pleased that he had a student who has traveled the world as a member of Bayanihan, the National Dance Company of the Philippines, and has visited many museums. (Nina, like her four older sisters, was a member of the famed Bayanihan Dancers.)

“He was my mentor; he was determined to make me follow his footsteps,” she said.

Paras-Perez may have opened some doors, but Nina was one conscientious student who was willing to work hard to prove her worth, starting as a curatorial assistant for contemporary art at the Cultural Center of the Philippines.

In 1981, she came to New York, as a recipient of Columbia University’s prestigious President’s Fellowship, and studied Art History and Archaeology at leading to the Ph.D. While she was previously avoiding the route to a Ph.D., Nina’s educational background, by this time, was so sharply focused on art history, there was no turning back. “I kept getting deeper and deeper into it.”

On the way to earning her Ph.D., she became a Graduate Fellow at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “I did an exhibit for them on Indonesia, and they published my first book Art of Island Southeast Asia in 1994 although I didn’t have a Ph.D. yet.”

Over the years followed more academic recognition, fellowships, research and book projects.

She is married to Kendal Baker, a native New Yorker she met in graduate school at Columbia. She and Kendal, who was formerly vice president for International Corporate Finance at the Union Bank of Bavaria, have two daughters: Phoebe, a theatre major; and Julia, a junior at the College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts.

Where the gold came from

“I was away studying abroad,” Nina recalled, when Philippine gold was being talked and written about in trickles in the 1960s. One of the early chroniclers was American anthropologist H. Otley Beyer.

“He published a summary of archaeological work on the Philippines from 1920s. He has a list of all gold collections before the war,” she said.

Her readings of Beyer’s work served to support and supplement whatever information she had heard from her father, the mining engineer. “My father walked me through the history of mining in the Philippines.”

During the war in the 1940s, many of the earlier gold collections disappeared. A couple of possibilities emerged, said Nina. Some were kept in hiding, but many were melted by the Japanese and used as currency to support the war.

There was a dearth in information around the 1950s, as the Philippines engaged in a process of post-war reconstruction and nation-building. “It wasn’t clear (what happened),” she said.

Sometime in the 1960s, some Filipinos began to “quietly” collect pre-colonial gold. The architect Leandro Locsin and his archaeologist wife Cecilia Locsin was one of them. The late artist-businessman Fernando Zobel de Ayala y Montojo whose family later founded the Ayala Museum, was an enthusiastic collector of Philippine art. Nina became the director of the Ayala Museum in 2000. The Locsin’s gold collection now forms the Ayala Museum’s gold collection, which is the core of the Asia Society’s gold exhibit.

In one of her presentations, Nina recounted the story of “Berto” who discovered a gold hoard near Butuan city in northeast Mindanao. He had a gut feeling they might be valuable so he stashed the hoard in a sack by covering it with bananas. His collection found its way into private hands.

Nina is currently on the faculty of CUNY’s Borough of Manhattan Community College teaching three sections of an introduction to Asian Art History in addition to being Ayala’s Special Consultant for International Operations and co-curator of the Philippine gold exhibit at Asia Society.

“People do not see how much work goes into it (the work of an art historian),” she said in reflection. “They see the exhibit or they listen to a lecture and that’s it. But behind every lecture are maybe 10 years of research.”

We lost touch with the Baker family and would very much appreciate to hear from them !

Norbert & Helga

Hallo Norbert und Helga, wie wunderbar von Dir zu hören! Kendal und ich reden nur zu versuchen, wieder zu verbinden! Bitte mailen Sie uns an kfbaker@usa.com oder fcapbaker@yahoo.com. Sie können Kendal auch hier erreichen – http://www.octagon-realty.com/contact.htm –

wärmste Wünsche für 2017, Nina