Filipina doctor Metty Pellicer fearlessly finds herself in America (Part 1)

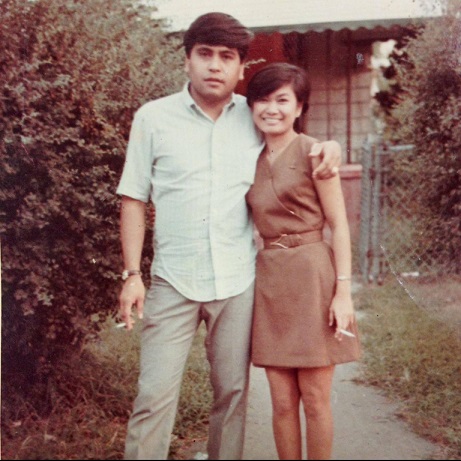

The author with (now deceased) husband John Pellicer, a pillar of the Filipino American community of Georgia. ‘Smoking was cool then.’

In high school I was an interna at the Colegio de Santa Isabel. It was heretic for a colegiala, especially an interna, to study at the University of the Philippines. I thought, had my mother gone crazy? Unlike my mother, I did not have the audacity to see myself as a doctor, especially one graduating from the UP. Her idea took my breath away! UP was considered too liberal, and dangerous to the reputation of young women. But it was also the premier national university. It had an international reputation for academic excellence. And since Mama thought that I could, I was daredevil enough to believe, that indeed I could.

I found out the study was too long and seeking admission was nerve-wracking. Out of over 800 applicants, only about 100 were admitted. In the last year of pre-Med, I had a crisis of confidence. I tried to persuade Mama to let me switch. I said I had enough credits to continue with BS Chemistry, and I could graduate in a year. But Mama would have none of it. She put her foot down, and there would be no argument. That was how I became a doctor.

However, shortly after graduation, I had an epic quarrel with Mama, and impulsively, I decided to leave home. I came to America. I had no idea what I was getting myself into.

My grand rebellion was made possible by a shift in U.S. immigration policy.

The civil rights movement of the ‘60s influenced the passage of The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (Hart-Celler Bill). It abolished the national origins quota and replaced it with the family reunification and skills preference system. Doctors, nurses, teachers and engineers were among the skills preferred for entry.

Under the Exchange Visitor Program, I obtained a J-1 visa in two weeks. There were recruiters aplenty who were aggressive in pursuing professional candidates for a fee. I was not about to ask Mama for money, I was still too hurt and angry after our quarrel. I turned to my best friend’s wealthy father for financing. I borrowed my application fee, airfare, and spare change and promised to pay him in monthly installments for a year.

At the Atlantic Station neighborhood in Atlanta where Metty, a young doctor of Psychiatry, lived in a condo across the lake.

After the flurry of activity of getting all the documents in order, I finally had a moment to reflect on the enormity of what I was about to do. I had never been on a plane before, I had never been out of the country and I had never traveled anywhere in the Philippines by myself, and here I was uprooting myself from all that was familiar. I was leaving my family, to go across the ocean to another land on the opposite end of the earth. I was afraid.

And then it hit me, a profound sadness and sense of loss, and anxiety.

Ravenswood Hospital in Chicago was the first to offer me an internship position. I had no idea where Chicago was. The only thing I knew about it was the news of mass murder of nurses in a Chicago hospital. A Filipina nurse survived the massacre, because she hid under a bed, I still remember her name, Corazon Amurao. I was scared and my resolve wavered. But as John Wayne said, “Courage is when you are afraid, but you saddle anyway!”

Fortunately, I didn’t have to test my courage. Unbeknownst to me, my sisters, who worried for me, told Mama. At the airport my mother arrived to see me off and gave me her blessing, plus extra $200 for pocket money.

Having received my mother’s forgiveness and blessing, I regained my confidence and spirit of adventure. And I saddled away with all my material possessions in one suitcase and $250 in my pocket. I embarked on the grandest adventure of my life.

Let me remind you classic stories about what it was like in the beginning. Carrying that infamous big brown envelope with our chest X-ray, like it was a matter of life and death. And that announced to everyone that we were FOBs (fresh off the boat). Each time I reenter the U.S. from one of my travels, I smile at someone with this brown envelope. Cradled in the chest, as if protecting it from all perils, I remember what it was like, to go through U.S. Customs for the first time.

As new immigrants, our initial experiences were excruciating and humiliating, but we managed to find humor in it.

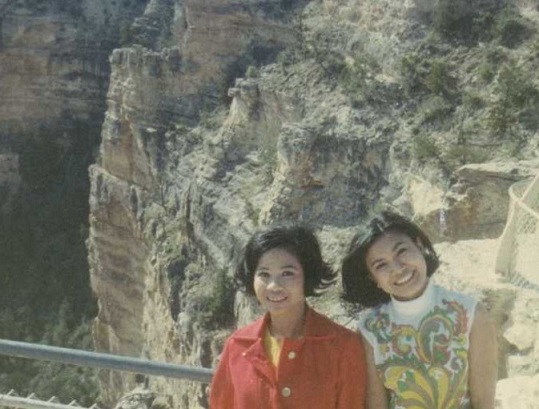

With classmate from the UP College of Medicine, Noy Calderon-Panahon (left), also a psychiatrist, in Buffalo.

Eating was not a simple act. What did we do with cereals for breakfast? We picked the dry morsels and ate it like peanuts. And then, we drank the milk. We thought we were cool to order to-go. We couldn’t understand why we were asked over and over what we wanted to-go. We ordered ham-boor-jeer, and we got a befuddled look. It was intimidating having to choose from so many unfamiliar condiments, when ordering a sandwich, or salad. Embarrassed and confused, we ended up with a tasteless meal. But in no time at all, hotdogs, and apple pie, and Thanksgiving turkey became staples on our table together with Lechon, Relyenong Bangus, and Adobo.

And who could forget the wonder of our first snowfall?

We have endless stories about the language and our accents. I was infamous on the tennis court for a word I’d shout after hitting a bad shot. But I said it like bedsheets, and everyone laughed. I couldn’t get a Black child to answer my question about his frequency of urination, until someone suggested I use the word “pee.” Many of my male classmates thought that they were Americanized, after learning the words, “fart”, “piss,” where’s the “john”, “be there or be square” and the unprintable ones, which I will not mention, but we all know them. And yet many Americans were surprised that we could already speak English shortly after arrival, and asked how we learned it. Johnny, my late husband, had a smart answer to this. He’d say, “I hung out with all the pretty flight stewardesses and talked with them all the way over.”

It was hard to be different. We thought we knew, from consuming popular American movies, magazines, and music. But we had confusing encounters in every turn.

In filling out application forms, I had to choose a race category. I was asked to check among White or Black, Asian, or Pacific Islander. The experience was profoundly existential. What am I? It threw me into an identity crisis. I did not feel I belonged to any of these categories. Filipinos look Asian, like Malaysian, Indonesian, Burmese, or Cambodians but we have nothing more in common with them. They are Buddhists or Muslims, and their culture and lifestyle is influenced by these eastern religions. We are Catholics, and similarly religion influenced, but we identify with the lifestyle and culture of the U.S. and Western Europe, but we don’t look like them. And although our surnames are Spanish, we don’t speak Spanish, instead we speak 99 dialects and languages. We could not understand each other across the Filipino language spectrum. But we could in English. Though we share culture and religion and colonial experience with Mexico, South America, Cuba and the Spanish Caribbean, we do not share their common language. Neither did Pacific Islander fit. We look like them but they are Polynesians, and Hawaiians. We don’t dance the hula, but the tinikling. We’re not White, but not Black either and certainly not American Indian or Eskimo.

NEXT: A bill in Congress paved the way for my citizenship

(C) 2017 The FilAm