Second-gen FilAms and the constant struggle to prove their parents’ move to America was ‘not in vain’

By Christian CatiisBeing raised by immigrant parents in the suburbs of a predominantly Caucasian neighborhood, I struggled with preserving my Filipino identity.

My Filipino mother had her sight set on emigrating to the U.S to accomplish her American Dream. Unknown to her at the time, she would later set a foundation of success not only for herself but the children she would be raising.

There was not much in her luggage when she came to America, but she made it up with the knowledge of what spices were necessary for a delicious Sinigang, a language that would make lasting friendships with her Filipino co-workers, and the drive for ambition many Pinoys and Pinays abroad are known for.

And as I embark on adulthood, I look at my parents’ life and try to embrace some lessons shaped by our Philippine heritage. Being raised in the United States brings with it a certain cultural responsibility to exemplify what being both a Filipino and an American truly is.

Being able to speak Tagalog, the main language of the Philippines, I was placed in ESL (English as a Second Language) classes. My primary school teachers explicitly told my parents to “only speak to him in English.”

However, now that I’m in my early 20s, I struggle with not only speaking Tagalog, but truly grasping what it is to be a Filipino. It’s difficult to really maintain a certain type of heritage when you are no longer living in the country itself and have only your older relatives as guideposts.

Cultural identity, like the plethora of tastes in Filipino cuisine and the multicolored spectrum of our festivals, is not one-dimensional. Defining the Filipino character derives from a multitude of ranges such as those who were born in the country itself, those whose romantic partner is a Pinoy/Pinay and have assimilated into the culture and customs, and those like me, whose connection is of family lineage.

In the pursuit of further understanding plural identities, I’ve interviewed fellow FilAm students in my school to see exactly how Filipino heritage is preserved and how being raised Filipino in the U.S has influenced their outlook and perspective.

What does being Filipino mean to you?

Cody Lucinario: I feel like the word “Filipino” is a composition of everything, whether it be the camaraderie, the emphasis on family, or the wonderful food we are so proud to share. It also means just being myself—spreading what I know of our culture and tradition, but willing to make new and open-minded traditions along the way. It is to be proud of what I am and to not be afraid to admit that being Filipino isn’t everything, but that it is my start.

Camille Duenas: It comes down to whether or not a person identifies as a Filipino based on his/her personal criteria. No sense in calling someone Filipino if he/she doesn’t want to think of him/herself as such. Likewise, no sense in telling someone what his/her identity is.

Bethany Jukuy: It simply means having a sense of community–to always help others in need and be friendly with others.

What have your parents done throughout your life to preserve the Filipino culture?

Cody Lucinario: My parents have given us plenty of our Filipino heritage: brought us to the Philippines, cooked traditional dishes, as well as taught us here and there what kind of folklore they had heard growing up.

Camille Duenas: The most obvious that comes to mind is food. Chicken Adobo, (made with Magic Sarap, of course) Lechon, and Champorado are just some of the foods I’ve grown up eating.

Bethany Jukuy: Other than Simbang Gabi around the holidays, and teaching me Tagalog here and there, my parents haven’t really continued many Filipino traditions here in the U.S.

How have your parents’ culture affected your perspective on American privilege?

Cody Lucinario: The privileges I have here in the U.S. weren’t present in the Philippines for them, and I understand that. I appreciate how hard they worked to get here, and living my life now in America, it is vastly different. My parents worked hard for a reason—it was so we, my sister and I, didn’t have to face the same struggles as they did growing up.

Camille Duenas: For all the improvements that the Philippines has in its cities, the fact remains that it is still a Third World country. The people don’t have many of the luxuries that we have. Health care isn’t as effective because they don’t have access to the same medications and technology as Americans are privy to.

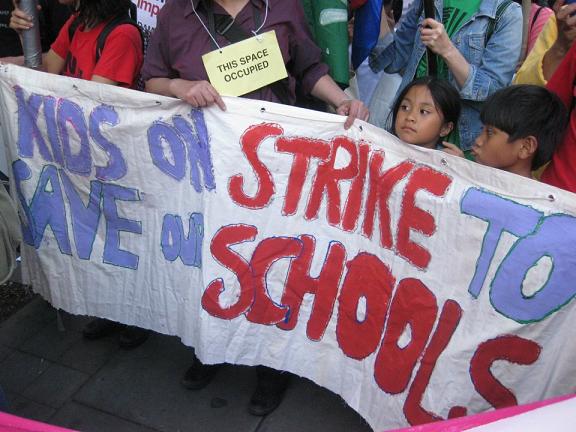

Bethany Jukuy: My parents have passed on their beliefs of working hard and competing to be one of the best when it comes to work. I feel as if I have to work harder to show them that moving to America was not in vain.

What did you learn about the value of education?

Cody Lucinario: I take into account what they have taught me, such as respecting your elders and how to value your education—these things I have carried on throughout my adulthood.

Camille Duenas: My mother constantly stresses to me that her family did not always have the funds to formally educate the entire family and that she envied those who could afford to do so. More recently, when she believes that I’m not taking my studies seriously, she says that education is the only thing that she and my father can give to me.

Bethany Jukuy: In their 20s, my parents held school as the top priority because it was emphasized by their parents in order (for them) to work in America. They were not allowed to date, nor were they allowed to dorm at their colleges. This was to prevent distraction from studying. As a young adult living in the U.S, school is still my top priority. However, I place less emphasis on it and focus on creating my own identity through self-improvement.

What about religion?

Cody Lucinario: Sometimes it’s hard to get away from their religious bias, so I often relied on what I think and what I’ve learned from different sources instead.

Camille Duenas: I admire the devotion to the Church that Filipinos have, even in times of hardships. They don’t lose faith as I’ve seen many Americans do. However, I must admit that they have an almost childlike belief, at least, from what I’ve seen. They blindly follow the law of the church without understanding why, and in doing so, can sometimes be aggressive in their missionary work. For example, how some children ironically turn away from the church because their parents were too forceful in Catholic education.

Bethany Jukuy: Religion was heavily emphasized growing up such as when it came to prayer and going to church. My viewpoint now is a bit different–as long as I put the principles/beliefs of the church into action, I’m generally satisfied with who I am.

Were you ever ashamed or insecure of your family’s lifestyle?

Cody Lucinario: Sometimes, when you’re welcomed to a new society, a new culture, there is often a friction you must overcome before you can be ‘assimilated,’ or for a better term, accepted. This occurred back in elementary school, as bringing rice and Filipino food for lunch every day didn’t exactly help my case in trying to fit in.

Camille Duenas: When I was much younger, I was very proud to identify as an American. I was not particularly ashamed of being Filipino so much as I was ashamed of being Asian in general.

Bethany Jukuy: I haven’t really had experiences with struggling with my identity as a Filipino. I don’t necessarily believe that American assimilation prevents preserving cultural heritage.

Describe how being American affects cultural heritage?

Cody Lucinario: Often people tend to have the idea that in order to fit in, you must abandon cultural heritage. However, I personally feel like that is similar to a paradox. If America, by definition, is a country of immigrants, then why must we abandon our culture?

Camille Duenas: Assimilation and cultural preservation often seem to contradict each other. It’s difficult when your family raises you one way and society (and friends) treat you another way. Who do you believe? What do you believe? The fact of the matter is, assimilation and preserving cultural heritage are difficult for the second- generation because we are neither fully one nor the other. We are both.

Bethany Jukuy: Granted, you grow up with the attitude of the country you are brought up in, but I also think it is the choice/responsibility of the older generations to pass on the culture.

Like his subjects above, Chris Catiis is a student at Ramapo College of New Jersey. Chris is studying to be a nurse. His writings have appeared in sites, such as Elite Daily and Thought Catalog. He is passionate about Asian-American Pacific Islander identity and racial diversity issues.