A region in Turkey where no violence or hatred toward others exists

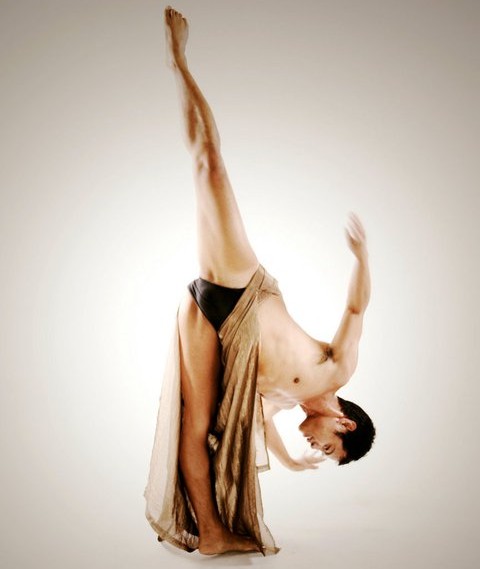

Author takes a selfie before climbing a steep staircase inside one of Cappadocia’s cave monasteries.

We know very well that Christianity has its roots in the Holy Land of Israel, but it may not be as widely understood that as an established religion and social institution, Christianity actually first blossomed in the ancient lands of Asia Minor, what is today known as Turkey. This is something my family learned on yet another excursion to that fascinating country once called Anatolia in past centuries.

On only our second day in the Turkish capital city of Ankara, our host, Philippine Ambassador to Turkey Maria Rowena Sanchez, advised us to visit Cappadocia, a region some three hours southeast of Ankara. We left early in the morning by car to journey to the place which is actually a large, isolated plateau in central Turkey. The landscape along the highway revealed mostly rocky fields with an occasional sight of shepherds herding goats and sheep.

When we arrived at Cappadocia, our driver-guide directed us to look towards the surrounding hills where there were several tall odd-shaped rock formations which resembled fairy chimneys. We soon learned that the rocks forming these structures were formed out of ash emitted by many volcanic eruptions which struck this region continuously from the Stone Age. These structures have also been used as homes by ancient people who crafted active societies out of this fascinating geological makeup.

We came upon the site of one of Cappadocia’s mystical underground cities, which was believed to have first been laid out by the Hittites around 2000 BC. We could see how centuries ago there were people who made a living amongst the rocks through the large carved holes which made the chimney structures appear as if they were giant beehives from a distance. What was most intriguing was learning how early Christians carved shelters and hiding places within these “beehive caves” to escape persecution from the Roman Empire during the 4th century AD.

The Cappadocian Fathers who came of age during the 4th century were influential in the carving and design of the several “cave monasteries” within the underground cities we explored. They are regarded as among the world’s first religious leaders who adopted the practice of bestowing sainthood upon others. Perhaps most significantly, they were also instrumental in the development of early Christian theology.

We learned that one of the great saints of that era was St. Basileios of Caesarea (329-379), simply known as Basil. Under his leadership, many of Cappadocia’s first monasteries were built in the region, becoming refuges of solitude for Christian monks who would contribute to the advancement of Christian spiritual and intellectual thinking, before the advent of state-sanctioned Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant churches in later centuries.

History also points out that St. Basil’s most valuable gift to the growth of the Christian religion was initiating the practice of common prayer, which is today a part of everyday church life, regardless of which denomination.

St. Basil founded the cenobitic lifestyle, which is communal living in the monastic hierarchy. He observed the many hermits living in his region, and then persuaded them to fellowship with other devout worshippers at the monasteries as he taught that a secluded life was counterproductive both to the individual and to society as a whole.

Given the “isolated” location of the plateau area of Cappadocia, I could understand how the monks and early Christian believers would feel relatively safe from Roman soldiers hunting for them. It was interesting to learn that the Christians who lived and worshipped within these cave monasteries enjoyed a much more advantaged lifestyle especially when compared to their brethren living in other places such as Syria and Egypt. Here in Cappadocia, there was no hatred or violence committed against fellow believers, open worship was tolerated, even encouraged, and the sick and elderly were taken great care of. It was truly depressing to think how in one of history’s greatest twists and ironies, as Christian societies evolved from underground movements to state-sanctioned entities, religious persecution, warfare and bloodshed would elevate most notably during the Middle Ages in the name of the very principles espoused by early Christians. History surely still has much to teach us.

Along with some jolly Filipino travelers whom we got to meet by chance, we braved steep rock staircases to view some of the small worship sites. Walking inside a few of them actually felt as if we were in genuine mini-cathedrals built within a cave.

To my surprise, we saw interior Byzantine-era mosaic art depictions of religious icons Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary and his disciples, such as St. Peter, that were all coated on the walls and ceilings of these “cave monasteries.” Viewing the mosaic religious art together with a few devout tourists praying here imbued me with an appreciation for the philosophy of hope and compassion which are central to Christianity, an enduring legacy for which the Cappadocian Fathers would always be remembered.

Great story, great place to visit. Thank you.